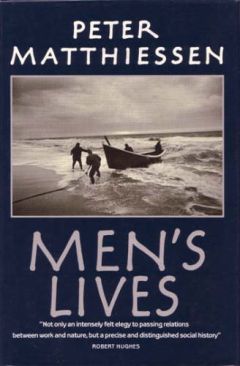

Matthiessen, Peter. Men’s Lives: The Surfmen and Baymen of the South Fork. New York: Random House, 1986.

Peter Matthiessen has written some of the greatest natural history and ethnographic studies of the modern era, including Wildlife in America and The Tree Where Man Was Born. In Men’s Lives, the author traces his own roots in the fishing communities of Long Island’s north coast.

While working on his first novels in the 1950s Matthiessen supported his new family as a surfman, plunging a high-backed wooden dory through the booming Atlantic swells to set gill nets for cod, hake, and especially the profitable striped bass or rockfish, a species that formerly migrated through Long Island Sound in the millions. On returning to the South Fork after a lifetime of wandering the globe, Matthiessen encounters a dying way of life, peopled by fishermen whose livelihoods have become anachronisms due to three pervasive influences: the growth of the moneyed suburbs from New York City and the resulting influx of resentful sportfishermen; the appearance in the 1970s of gargantuan factory fishing ships from Asia and Europe, trailing monofilament purse seines miles long that indiscriminately “harvest” everything in their paths; and, perhaps most destructively, the gradual poisoning of the coastal spawning grounds of anadromous and delta-breeding fishes. This last factor, when coupled with the massive loss of wetlands through coastal development over the last fifty years, has left little habitat where fish stocks may recover their numbers.

The tremendous growth of the American “megalopolis” along the Atlantic shore from Boston to Alexandria has lead to a concurrent increase in industrial discharge, agricultural and urban runoff, sewage and toxins spills, and massive water extraction for industrial agriculture and cities. As the viability of Atlantic species declines, the population of fish-eating people along the shore increases; the resulting escalation of competition for a dwindling resource will naturally (according to the unforgiving maxims of social Darwinism and the consumer economy) favor the massive, the mechanized, and the politically influential.

Matthiessen records with somber precision the conflicts engaged in by the traditional Long Islanders with the powerful sportfishermen’s organizations and the state game department (the surfmen consider themselves New Englanders, and disassociate themselves, for obvious reasons, from the rapacious upstarts of suburban New York City), and notes that while these potential allies squabble over a dissipating resource, the real enemies, the foreign fish factories, the drainers of wetlands, and the pollutive industrial/agribusiness cabals, continue to assure that neither camp will reap the sea’s bounty for much longer.

Emotions run high as the surfmen see their ancient way of life inexorably collapsing; at a hearing with their unctuously dapper state representative, one fisherman shouts that

“‘If you ever done a day’s work fishin, you’d never survive it! How come you never come out here, went fishin with us, never learned the truth? This man here’—he pointed to Captain Bill—‘he can tell you more about fishin than all them people you listen to put together! You’re just out for yourself, out for your own ambitions, you don’t care about the harm you done to families that’s been fishin for three hundred years!’”

The fishermen glory in their way of life, in the hard, honest work and in their connection with the sea and the past, and they gaze apprehensively at the incomprehensible new world they see bearing down on them: “’If we wanted eels or clams or fish, we always got ‘em fresh, cause there was no problems gettin stuff to eat. Them days people didn’t kill themselves like they do t’day, ‘cause there was no problems. Whatever you wanted to catch, there was plenty of it.’”

Matthiessen sees little hope for the traditional fishermen of Long Island, and appropriately writes his book as a eulogy, aglow with reminiscence of a proud and storied tradition. In doing so he returns to a central theme of all of his works: that what we are doing and where we are going with a mass-produced, self-destructive, technocratic society based on the entrenchment of enforced homogeneity will result in the total disintegration of our natural heritage and the concomitant dehumanization of Western civilization. Traits by which we have long defined ourselves—virtues such as wisdom, humility, persistence, and personal liberty—fall by the wayside in our rush toward uniformity and mechanism, and Men’s Lives is as much a lament for the decline of traditional American values as for the dying surf fishing culture of Long Island. “Independence costs you a lot of money,” said one of the last dory fishermen to the author. “I starved myself to death for independence when I could have made good money at a trade. You ever seen anybody yet get fired from fishin? No, no! You’re just glad to find somebody stupid enough to go with you.”

Peter Matthiessen has written some of the greatest natural history and ethnographic studies of the modern era, including Wildlife in America and The Tree Where Man Was Born. In Men’s Lives, the author traces his own roots in the fishing communities of Long Island’s north coast.

While working on his first novels in the 1950s Matthiessen supported his new family as a surfman, plunging a high-backed wooden dory through the booming Atlantic swells to set gill nets for cod, hake, and especially the profitable striped bass or rockfish, a species that formerly migrated through Long Island Sound in the millions. On returning to the South Fork after a lifetime of wandering the globe, Matthiessen encounters a dying way of life, peopled by fishermen whose livelihoods have become anachronisms due to three pervasive influences: the growth of the moneyed suburbs from New York City and the resulting influx of resentful sportfishermen; the appearance in the 1970s of gargantuan factory fishing ships from Asia and Europe, trailing monofilament purse seines miles long that indiscriminately “harvest” everything in their paths; and, perhaps most destructively, the gradual poisoning of the coastal spawning grounds of anadromous and delta-breeding fishes. This last factor, when coupled with the massive loss of wetlands through coastal development over the last fifty years, has left little habitat where fish stocks may recover their numbers.

The tremendous growth of the American “megalopolis” along the Atlantic shore from Boston to Alexandria has lead to a concurrent increase in industrial discharge, agricultural and urban runoff, sewage and toxins spills, and massive water extraction for industrial agriculture and cities. As the viability of Atlantic species declines, the population of fish-eating people along the shore increases; the resulting escalation of competition for a dwindling resource will naturally (according to the unforgiving maxims of social Darwinism and the consumer economy) favor the massive, the mechanized, and the politically influential.

Matthiessen records with somber precision the conflicts engaged in by the traditional Long Islanders with the powerful sportfishermen’s organizations and the state game department (the surfmen consider themselves New Englanders, and disassociate themselves, for obvious reasons, from the rapacious upstarts of suburban New York City), and notes that while these potential allies squabble over a dissipating resource, the real enemies, the foreign fish factories, the drainers of wetlands, and the pollutive industrial/agribusiness cabals, continue to assure that neither camp will reap the sea’s bounty for much longer.

Emotions run high as the surfmen see their ancient way of life inexorably collapsing; at a hearing with their unctuously dapper state representative, one fisherman shouts that

“‘If you ever done a day’s work fishin, you’d never survive it! How come you never come out here, went fishin with us, never learned the truth? This man here’—he pointed to Captain Bill—‘he can tell you more about fishin than all them people you listen to put together! You’re just out for yourself, out for your own ambitions, you don’t care about the harm you done to families that’s been fishin for three hundred years!’”

The fishermen glory in their way of life, in the hard, honest work and in their connection with the sea and the past, and they gaze apprehensively at the incomprehensible new world they see bearing down on them: “’If we wanted eels or clams or fish, we always got ‘em fresh, cause there was no problems gettin stuff to eat. Them days people didn’t kill themselves like they do t’day, ‘cause there was no problems. Whatever you wanted to catch, there was plenty of it.’”

Matthiessen sees little hope for the traditional fishermen of Long Island, and appropriately writes his book as a eulogy, aglow with reminiscence of a proud and storied tradition. In doing so he returns to a central theme of all of his works: that what we are doing and where we are going with a mass-produced, self-destructive, technocratic society based on the entrenchment of enforced homogeneity will result in the total disintegration of our natural heritage and the concomitant dehumanization of Western civilization. Traits by which we have long defined ourselves—virtues such as wisdom, humility, persistence, and personal liberty—fall by the wayside in our rush toward uniformity and mechanism, and Men’s Lives is as much a lament for the decline of traditional American values as for the dying surf fishing culture of Long Island. “Independence costs you a lot of money,” said one of the last dory fishermen to the author. “I starved myself to death for independence when I could have made good money at a trade. You ever seen anybody yet get fired from fishin? No, no! You’re just glad to find somebody stupid enough to go with you.”