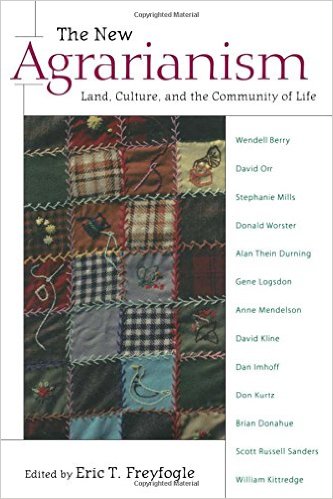

Eric T Freyfogle, editor. The New Agrarianism: Land, Culture and the Community of Life, Island Press/Shearwater Books, Washington, DC: 2001

In 1930 a group of a dozen intellectuals associated with Vanderbilt University in Nashville published a manifesto of political, cultural and economic thought entitled I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition. Spearheaded by such literary luminaries as Allen Tate, David Donaldson, Andrew Lytle, John Crowe Ransom and Robert Penn Warren, the “Agrarians” embodied the accumulated discontents of a region then still very much recovering from the devastation of war and occupation. The chief philosophic thrust of the book, in the words of Eric Freyfogle, the editor of The New Agrarianism: Land, Culture and the Community of Life, which is in some ways a modern, multiregional reincarnation of I’ll Take My Stand, dealt with the authors’ “alarm over the effects of industrialism and materialism on the mannerly, leisurely, humanistic culture they viewed as the South’s greatest treasure.” A similar generosity of spirit and outlook, nurtured by a hard-won freedom that itself depended upon munificence and commitment, once characterized all of America, and it is only though the insidious manipulations of the global corporate economy that the our liberties are at last beginning to wane. The new agrarians offer us an alternative.

Freyfogle enlists some of the finest environmental and agricultural thinkers in the country, including Wendell Berry, Donald Worster, William Kittredge and David Orr, and introduces his collection with an excellent essay of his own, “A Durable Scale.” “Agrarianism,” he tells us, “comes from the Latin word agrarius, ‘pertaining to the land,’ and it is the land—as place, home, and living community—that anchors the agrarian scale of values.” “By community,” says Wendell Berry,

“I mean the commonwealth and common interests, commonly understood, of people living in a place and wishing to continue to do so. To put it another way, community is a locally understood interdependence of local people, local culture, local economy, local nature.”

In short, everything that the modern impetus toward a unitary economy, “free trade,” community disintegration, and disconnectedness with the Earth is not. Whether labeled as industrialism, modernism or materialism, the danger is pervasive and omnipresent, readily seen in the subdivided farms, closed textile mills, uprooted families and accelerating devastation of the natural world that mark our land today. We have become lax and incautious in our fleeting ease; we have allowed our freedoms to incrementally trickle away like sand down an eroded ditch. To recapture the liberties that we once enjoyed—sovereignty, free will, independence—we will have to change our way buying, of thinking, and of living.

Wendell Berry, Kentucky farmer and poet, is perhaps the greatest exponent of the new agrarianism working today; he distils the essence of these wide-ranging, spirited essays in his own contribution, “The Whole Horse”, wherein he states that “agrarianism is primarily a practice, a set of attitudes, a loyalty, and a passion; it is an idea only secondarily and at a remove.” Like humanitarianism and environmentalism, then, the new agrarianism is both movement and mindset, a resuscitative ghost dance as revolutionary in its ideals as those of 1776.

Berry, who has been publicly pondering the implications of living rightly on the land for over fifty years, neatly illustrates the disparities in the two worldviews of agrarianism and industrialism:

“Whereas industrialism is a way of thought based on monetary capital and technology, agrarianism is a way of thought based on land.

Agrarianism, furthermore, is a culture at the same time that it is an economy. Industrialism is an economy before it is a culture. Industrial culture is an accidental by-product of the ubiquitous effort to sell by-products for more than they are worth.”

The cyclonic forces of change that swept the country in the 20th century, despite its hysterically anti-communist policies, emphasized as a central national goal the collectivization of the businesses of agriculture, mining, timber, distribution and manufacture as small farmers and independent businessmen were forced out of operation by economic strategies invariably favoring the large over the small. This monopolistic coercion is approaching its zenith (predicating, according to some contributors here, its final failure) with the advent of that ultimate statist impersonality, the globalized economy. Indeed, the “Statement of Principles” of I’ll Take My Stand accurately predicted our current dilemma of centralized, external economic control: “The true Sovietists or Communists … are the industrialists themselves. They would have the government set up an economic super-organization, which would in turn become the government.” Prescient thinking for 1930, before even the formation of the United Nations, to say nothing of GATT, NAFTA and the WTO.

Agrarianism is inherently conservative—mindful of the land, its inhabitants and productions, and dismayed by the frivolous waste of topsoil, forests, farmland, and ecosystems that we see almost everywhere today. “Conservative” and “conservationist” are clearly of common etymological origin, yet who in Washington, describing themselves as conservatives, can fairly lay claim to both titles? For it is the sad nature of representative government today for politicians to work unflaggingly for the most powerful members of their constituencies, those whose millions cyclically fuel those garish displays of election-year ego and vindictiveness. Agrarians wish to diminish the power and influence of corporate control over the republic by taking matters into their own hands; in this regard, they embody many of the values that America was formerly known for.

These essays speak of a growing dissatisfaction with the corporatist status quo: of community-supported agricultural partnerships that supply urbanites with clean fresh produce without the benefit of industrial toxins; of citizen initiatives to restore and protect river watersheds; of farmers who break free of extension-agent rhetoric based on machinery, debt and herbicides and adopt new/old methods to conserve topsoil and promote diversity of crops and rotations; and of the growing number of families who meet many of their food needs with a private garden or orchard (gardening for the revolution!).

Make no mistake: this collection of stories and revelations from the hollowed heartland of rural America quietly advocates a large-scale revolt against the domineering prerogative over our lives: the international corporations, those faceless powers whose endless lust for profit threatens to strangle what is good and unique in the national character. Written in turn by tenured academics, cultural historians, Amish farmers and urban activists, The New Agrarianism stakes a claim as one of the first great social documents of the new century. By learning from the past how best to profit in the future, agrarian principles promise to better the natural and human world by merging aspects of the two in a new vision for the countryside upon whose bounty we all depend.

In 1930 a group of a dozen intellectuals associated with Vanderbilt University in Nashville published a manifesto of political, cultural and economic thought entitled I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition. Spearheaded by such literary luminaries as Allen Tate, David Donaldson, Andrew Lytle, John Crowe Ransom and Robert Penn Warren, the “Agrarians” embodied the accumulated discontents of a region then still very much recovering from the devastation of war and occupation. The chief philosophic thrust of the book, in the words of Eric Freyfogle, the editor of The New Agrarianism: Land, Culture and the Community of Life, which is in some ways a modern, multiregional reincarnation of I’ll Take My Stand, dealt with the authors’ “alarm over the effects of industrialism and materialism on the mannerly, leisurely, humanistic culture they viewed as the South’s greatest treasure.” A similar generosity of spirit and outlook, nurtured by a hard-won freedom that itself depended upon munificence and commitment, once characterized all of America, and it is only though the insidious manipulations of the global corporate economy that the our liberties are at last beginning to wane. The new agrarians offer us an alternative.

Freyfogle enlists some of the finest environmental and agricultural thinkers in the country, including Wendell Berry, Donald Worster, William Kittredge and David Orr, and introduces his collection with an excellent essay of his own, “A Durable Scale.” “Agrarianism,” he tells us, “comes from the Latin word agrarius, ‘pertaining to the land,’ and it is the land—as place, home, and living community—that anchors the agrarian scale of values.” “By community,” says Wendell Berry,

“I mean the commonwealth and common interests, commonly understood, of people living in a place and wishing to continue to do so. To put it another way, community is a locally understood interdependence of local people, local culture, local economy, local nature.”

In short, everything that the modern impetus toward a unitary economy, “free trade,” community disintegration, and disconnectedness with the Earth is not. Whether labeled as industrialism, modernism or materialism, the danger is pervasive and omnipresent, readily seen in the subdivided farms, closed textile mills, uprooted families and accelerating devastation of the natural world that mark our land today. We have become lax and incautious in our fleeting ease; we have allowed our freedoms to incrementally trickle away like sand down an eroded ditch. To recapture the liberties that we once enjoyed—sovereignty, free will, independence—we will have to change our way buying, of thinking, and of living.

Wendell Berry, Kentucky farmer and poet, is perhaps the greatest exponent of the new agrarianism working today; he distils the essence of these wide-ranging, spirited essays in his own contribution, “The Whole Horse”, wherein he states that “agrarianism is primarily a practice, a set of attitudes, a loyalty, and a passion; it is an idea only secondarily and at a remove.” Like humanitarianism and environmentalism, then, the new agrarianism is both movement and mindset, a resuscitative ghost dance as revolutionary in its ideals as those of 1776.

Berry, who has been publicly pondering the implications of living rightly on the land for over fifty years, neatly illustrates the disparities in the two worldviews of agrarianism and industrialism:

“Whereas industrialism is a way of thought based on monetary capital and technology, agrarianism is a way of thought based on land.

Agrarianism, furthermore, is a culture at the same time that it is an economy. Industrialism is an economy before it is a culture. Industrial culture is an accidental by-product of the ubiquitous effort to sell by-products for more than they are worth.”

The cyclonic forces of change that swept the country in the 20th century, despite its hysterically anti-communist policies, emphasized as a central national goal the collectivization of the businesses of agriculture, mining, timber, distribution and manufacture as small farmers and independent businessmen were forced out of operation by economic strategies invariably favoring the large over the small. This monopolistic coercion is approaching its zenith (predicating, according to some contributors here, its final failure) with the advent of that ultimate statist impersonality, the globalized economy. Indeed, the “Statement of Principles” of I’ll Take My Stand accurately predicted our current dilemma of centralized, external economic control: “The true Sovietists or Communists … are the industrialists themselves. They would have the government set up an economic super-organization, which would in turn become the government.” Prescient thinking for 1930, before even the formation of the United Nations, to say nothing of GATT, NAFTA and the WTO.

Agrarianism is inherently conservative—mindful of the land, its inhabitants and productions, and dismayed by the frivolous waste of topsoil, forests, farmland, and ecosystems that we see almost everywhere today. “Conservative” and “conservationist” are clearly of common etymological origin, yet who in Washington, describing themselves as conservatives, can fairly lay claim to both titles? For it is the sad nature of representative government today for politicians to work unflaggingly for the most powerful members of their constituencies, those whose millions cyclically fuel those garish displays of election-year ego and vindictiveness. Agrarians wish to diminish the power and influence of corporate control over the republic by taking matters into their own hands; in this regard, they embody many of the values that America was formerly known for.

These essays speak of a growing dissatisfaction with the corporatist status quo: of community-supported agricultural partnerships that supply urbanites with clean fresh produce without the benefit of industrial toxins; of citizen initiatives to restore and protect river watersheds; of farmers who break free of extension-agent rhetoric based on machinery, debt and herbicides and adopt new/old methods to conserve topsoil and promote diversity of crops and rotations; and of the growing number of families who meet many of their food needs with a private garden or orchard (gardening for the revolution!).

Make no mistake: this collection of stories and revelations from the hollowed heartland of rural America quietly advocates a large-scale revolt against the domineering prerogative over our lives: the international corporations, those faceless powers whose endless lust for profit threatens to strangle what is good and unique in the national character. Written in turn by tenured academics, cultural historians, Amish farmers and urban activists, The New Agrarianism stakes a claim as one of the first great social documents of the new century. By learning from the past how best to profit in the future, agrarian principles promise to better the natural and human world by merging aspects of the two in a new vision for the countryside upon whose bounty we all depend.