Abbey, Edward. The Fool’s Progress: An Honest Novel. New York: Avon, 1990

The Fool’s Progress could have been written only in America, and only by Edward Abbey. A semi-autobiographical novel about a man who refuses to submit to modern commercial society, this book will be disturbing to some, offensive to others, and revelatory to a few. The author had often claimed that a book was a paper club to beat one’s enemies over the head with, and in this novel, the last published while he was still alive, he pulls out all stops to simultaneously enrage and fascinate his audience in the hope of blasting through their accumulated detritus of “political correctness” (an inherently repressive term) to jerk alive the emotions hiding beneath.

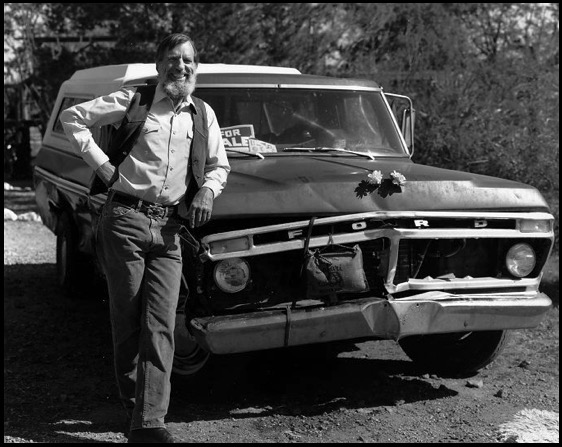

Opening in Tucson with the enraged departure of his (third) young wife, The Fool’s Progress traces the journey by pickup truck and through time of Henry Holyoak Lightcap, from the southwestern deserts of his heart back to his native home of West Virginia. After killing his noisy refrigerator with a .357 Magnum, Lightcap puts on Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony at ear-splitting volume, drinks off a half-quart of the Wild Turkey, and miserably dreams of past loves and his lost Appalachian home. In the morning, heavily hung over,

“Henry eats his breakfast, bleak and lonely, and makes his plans. Plug in phone, call welfare office, tell them he’s taking another leave without pay, they won’t mind. Visit the bank, empty checking account, pick up needed cash. Load up the old Dodge with camping gear, essential firearms, spare parts, a certain few books. Write a farewell letter to Elaine. Shoot the dog [dying of lung fungus]. Get in truck and point its battered nose eastward, toward the world of the rising sun and Stump Creek, West Virginia. Home. Only three thousand five hundred miles to go. Brother Will, I say to my shattered heart, my private little secret, here I come. Prepare thyself.”

Along the way, Lightcap stops to visit old friends from his disorderly youth (“the comforters”) in Arizona and New Mexico; he is asked several times to stay with them and continue his life in the West, but always he remains determined to reunite himself one last time with his estranged family. The urgency that drives Henry’s trek is finally revealed near the end of the novel when we learn that he suffers from a terminal illness, the gravity of which forgives his relentless habit of burning bridges behind him.

Throughout the voyage, “Everyman’s Journey to the East,” Henry takes in and digests—not only cheap beer—but the spectacle of what modern industrial-commercial-agricultural society has done to the country he plainly loves. The entirety of the book is suffused with a sense of the dying land, more obvious perhaps when seen through the eyes of the dying man. But Henry, though faced with a host of troubles that would drive more well-adjusted men to static despair (“I’ve lost my home, my wife and my job in the last forty-eight hours”), continues to exert an indomitably humorous approach to his plight, intimidating the pompous, challenging the ignorant, and as a philosophy major (“well, a second lieutenant”) searching always for some trace of an “ontological significance if any of sublunar existence. Such as it is. If it exists. Precisely the question.” Near Dodge City, Kansas, Henry and his delapidated dog Solstice (whom he declined to put down, “lacking the kindness to be so cruel”) together

“pass through a few acres of unplowed unimproved prairie, one remnant of that sea of grass which formally stretched from the Mississippi to the base of the Rocky Mountains. The open range. Where the buffalo roamed, where the deer and the antelope played for twenty thousand years. And then up from Texas came the mass herds of stinking shambling dung-smeared bawling bellowing bulge-eyed cattle. Followed by cowboys, beef ranchers, barbed wire, cross fencing, locked gates, private property, whores, bores and real estate developers.”

Despite these cranky environmental musings, Henry’s actions are not always immediately apparent as being what most would consider “eco-conscious.” Motoring along through New Mexico, Henry makes “(t)ime for my eight-course lunch: cheese, crackers, sixpack of beer. Not what the doctor ordered, precisely, but the habits of a lifetime may not lightly be discarded. ‘Dispose of Thoughtfully’ say the printed instructions on the sixpack. Thoughtfully I drop the first empty out the window two miles beyond Española. The can bounces along on the pavement before coasting to the shoulder of the road. Some kid with a sack will pick it up. Recycle that aluminum. Give a hoot.” For reasons such as this, The Fool’s Progress irritated many in the “environmental community” as an irresponsible gesture from a man many considered to be an ecological prophet. But Abbey never willingly accepted this role, as anyone who has read him extensively must attest, and despised being packed into the “nature writer” closet by reviewers. Despite his flippant and irreverent black humor, however, Abbey’s true convictions about the real threats facing the American land and the American soul continue to shine through. (Abbey littered public roads out of a philosophical certainty that is wasn’t the beer cans that were ugly, but the highways themselves, slashed across otherwise pristine countryside.)

At times a grimly realistic On the Road for the 21st century, the novel is rife with unsettling observations of our love affair with spiritual ruin. Rolling across rural Missouri Henry encounters

“…a half-mile-long feedlot in which imprisoned Herefords, Charolais, and black Angus beefburgers, on the hoof and more or less alive, standing room only, mill about under the sun on a carpet of mud, urine and manure … This is not farm country but an agricultural factory where not only the soil, air and water but living animals themselves, kine and swine, mammals like us, mothers with emotions similar to ours—love, lust, fear—are treated as raw raw-material for packaged meats. Enough to make a man a bloody vegetarian if he lets his mind dwell on it. Best not to dwell on it. Think of death not life the next time you stuff your chops with veal, sirloin, ham, bratwurst … I tremble for us Christians if there is a Christian god.

“Me and my dog. We think this way sometimes.”

It is not easy to classify this book, as it is not easy to classify the author, or anyone else of real interest. Henry Lightcap illuminates for us the best and worst potential of this country and its strange people, even as he points out the creeping perils to the land and to the human spirit. Impassively addressing the mysteriously slain corpse of his hermetic friend Morton Bildad, Henry outlines some of the troubles of our calamituous age:

“You’ll note I say nothing of the general state of human affairs. My current wife sleeping with a computer science professor … a computer fucking science professor! My friends mired in mortgages and indoor jobs and medical insurance, the hellhole of Africa, the black hole of Asia, the torture rack of Latin America, the glut and gloom and gluttony of North America, the grimy Weltschmerz of Europe, the depair of the whales in Oceania, the ghost dance of the grizzly bears, the death march of the elephants, the Doomsday machines over our heads—I tell you, Bildad, I realize now why the universe, as the astronomers have discovered, is receding from us at all directions at near the speed of light. Why? Red shift? No! Because of fear that’s why. We are the plague of the cosmos. The stars are not merely flying away, they are fleeing away, tripping away on little starfeet at a hundred and eighty thousand miles per second, running for their lives.”

Much later, limping along with his old truck through the industrial heart of the Midwest, Henry sees

“[O]il refineries appear, catalytic cracking plants, a thicket of pipes and stacks with flare-off fires brighter than the sunlight. Nostril-prickling smells float on the air, sly and sinister. Factory buildings of rusty red sheet metal, their windows broken, stand next to foundries and blast furnaces with brick chimneys sixty eighty feet a hundred feet high. Near each clanging workshop is a settling pond, a tailings dump, a slime pit filled with oily sludge, toxic solvents, pathogenic chemicals, black tars and industrial vomit roiled together in a marbled arabesque of brilliant, unforeseeable colors … Yes, and suppose this mad environment went on forever?”

Without the wilderness, Lightcap/Abbey seems to say, without the unspoiled remnants of our native country left intact, the mad environment we have brought down on ourselves and on everything else must one day overtake us. As with Henry’s doomed journey home, there will be no ultimate escape.

The Fool’s Progress could have been written only in America, and only by Edward Abbey. A semi-autobiographical novel about a man who refuses to submit to modern commercial society, this book will be disturbing to some, offensive to others, and revelatory to a few. The author had often claimed that a book was a paper club to beat one’s enemies over the head with, and in this novel, the last published while he was still alive, he pulls out all stops to simultaneously enrage and fascinate his audience in the hope of blasting through their accumulated detritus of “political correctness” (an inherently repressive term) to jerk alive the emotions hiding beneath.

Opening in Tucson with the enraged departure of his (third) young wife, The Fool’s Progress traces the journey by pickup truck and through time of Henry Holyoak Lightcap, from the southwestern deserts of his heart back to his native home of West Virginia. After killing his noisy refrigerator with a .357 Magnum, Lightcap puts on Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony at ear-splitting volume, drinks off a half-quart of the Wild Turkey, and miserably dreams of past loves and his lost Appalachian home. In the morning, heavily hung over,

“Henry eats his breakfast, bleak and lonely, and makes his plans. Plug in phone, call welfare office, tell them he’s taking another leave without pay, they won’t mind. Visit the bank, empty checking account, pick up needed cash. Load up the old Dodge with camping gear, essential firearms, spare parts, a certain few books. Write a farewell letter to Elaine. Shoot the dog [dying of lung fungus]. Get in truck and point its battered nose eastward, toward the world of the rising sun and Stump Creek, West Virginia. Home. Only three thousand five hundred miles to go. Brother Will, I say to my shattered heart, my private little secret, here I come. Prepare thyself.”

Along the way, Lightcap stops to visit old friends from his disorderly youth (“the comforters”) in Arizona and New Mexico; he is asked several times to stay with them and continue his life in the West, but always he remains determined to reunite himself one last time with his estranged family. The urgency that drives Henry’s trek is finally revealed near the end of the novel when we learn that he suffers from a terminal illness, the gravity of which forgives his relentless habit of burning bridges behind him.

Throughout the voyage, “Everyman’s Journey to the East,” Henry takes in and digests—not only cheap beer—but the spectacle of what modern industrial-commercial-agricultural society has done to the country he plainly loves. The entirety of the book is suffused with a sense of the dying land, more obvious perhaps when seen through the eyes of the dying man. But Henry, though faced with a host of troubles that would drive more well-adjusted men to static despair (“I’ve lost my home, my wife and my job in the last forty-eight hours”), continues to exert an indomitably humorous approach to his plight, intimidating the pompous, challenging the ignorant, and as a philosophy major (“well, a second lieutenant”) searching always for some trace of an “ontological significance if any of sublunar existence. Such as it is. If it exists. Precisely the question.” Near Dodge City, Kansas, Henry and his delapidated dog Solstice (whom he declined to put down, “lacking the kindness to be so cruel”) together

“pass through a few acres of unplowed unimproved prairie, one remnant of that sea of grass which formally stretched from the Mississippi to the base of the Rocky Mountains. The open range. Where the buffalo roamed, where the deer and the antelope played for twenty thousand years. And then up from Texas came the mass herds of stinking shambling dung-smeared bawling bellowing bulge-eyed cattle. Followed by cowboys, beef ranchers, barbed wire, cross fencing, locked gates, private property, whores, bores and real estate developers.”

Despite these cranky environmental musings, Henry’s actions are not always immediately apparent as being what most would consider “eco-conscious.” Motoring along through New Mexico, Henry makes “(t)ime for my eight-course lunch: cheese, crackers, sixpack of beer. Not what the doctor ordered, precisely, but the habits of a lifetime may not lightly be discarded. ‘Dispose of Thoughtfully’ say the printed instructions on the sixpack. Thoughtfully I drop the first empty out the window two miles beyond Española. The can bounces along on the pavement before coasting to the shoulder of the road. Some kid with a sack will pick it up. Recycle that aluminum. Give a hoot.” For reasons such as this, The Fool’s Progress irritated many in the “environmental community” as an irresponsible gesture from a man many considered to be an ecological prophet. But Abbey never willingly accepted this role, as anyone who has read him extensively must attest, and despised being packed into the “nature writer” closet by reviewers. Despite his flippant and irreverent black humor, however, Abbey’s true convictions about the real threats facing the American land and the American soul continue to shine through. (Abbey littered public roads out of a philosophical certainty that is wasn’t the beer cans that were ugly, but the highways themselves, slashed across otherwise pristine countryside.)

At times a grimly realistic On the Road for the 21st century, the novel is rife with unsettling observations of our love affair with spiritual ruin. Rolling across rural Missouri Henry encounters

“…a half-mile-long feedlot in which imprisoned Herefords, Charolais, and black Angus beefburgers, on the hoof and more or less alive, standing room only, mill about under the sun on a carpet of mud, urine and manure … This is not farm country but an agricultural factory where not only the soil, air and water but living animals themselves, kine and swine, mammals like us, mothers with emotions similar to ours—love, lust, fear—are treated as raw raw-material for packaged meats. Enough to make a man a bloody vegetarian if he lets his mind dwell on it. Best not to dwell on it. Think of death not life the next time you stuff your chops with veal, sirloin, ham, bratwurst … I tremble for us Christians if there is a Christian god.

“Me and my dog. We think this way sometimes.”

It is not easy to classify this book, as it is not easy to classify the author, or anyone else of real interest. Henry Lightcap illuminates for us the best and worst potential of this country and its strange people, even as he points out the creeping perils to the land and to the human spirit. Impassively addressing the mysteriously slain corpse of his hermetic friend Morton Bildad, Henry outlines some of the troubles of our calamituous age:

“You’ll note I say nothing of the general state of human affairs. My current wife sleeping with a computer science professor … a computer fucking science professor! My friends mired in mortgages and indoor jobs and medical insurance, the hellhole of Africa, the black hole of Asia, the torture rack of Latin America, the glut and gloom and gluttony of North America, the grimy Weltschmerz of Europe, the depair of the whales in Oceania, the ghost dance of the grizzly bears, the death march of the elephants, the Doomsday machines over our heads—I tell you, Bildad, I realize now why the universe, as the astronomers have discovered, is receding from us at all directions at near the speed of light. Why? Red shift? No! Because of fear that’s why. We are the plague of the cosmos. The stars are not merely flying away, they are fleeing away, tripping away on little starfeet at a hundred and eighty thousand miles per second, running for their lives.”

Much later, limping along with his old truck through the industrial heart of the Midwest, Henry sees

“[O]il refineries appear, catalytic cracking plants, a thicket of pipes and stacks with flare-off fires brighter than the sunlight. Nostril-prickling smells float on the air, sly and sinister. Factory buildings of rusty red sheet metal, their windows broken, stand next to foundries and blast furnaces with brick chimneys sixty eighty feet a hundred feet high. Near each clanging workshop is a settling pond, a tailings dump, a slime pit filled with oily sludge, toxic solvents, pathogenic chemicals, black tars and industrial vomit roiled together in a marbled arabesque of brilliant, unforeseeable colors … Yes, and suppose this mad environment went on forever?”

Without the wilderness, Lightcap/Abbey seems to say, without the unspoiled remnants of our native country left intact, the mad environment we have brought down on ourselves and on everything else must one day overtake us. As with Henry’s doomed journey home, there will be no ultimate escape.